Reprinted–nay, stolen from the band’s website whole cloth, out of fear it will be taken down there. (Hopefully they won’t force it to be taken down here. This is Dan Fan gold.)

Art is the music we make from the bewildered cry of being alive. ~Maria Popova

17 Apr 2022 Leave a comment

in General Posts Tags: pretzel logic, steely dan

Reprinted–nay, stolen from the band’s website whole cloth, out of fear it will be taken down there. (Hopefully they won’t force it to be taken down here. This is Dan Fan gold.)

17 Apr 2022 Leave a comment

in General Posts Tags: countdown to ecstasy, steely dan

Reprinted–nay, stolen from the band’s website whole cloth, out of fear it will be taken down there. (Hopefully they won’t force it to be taken down here. This is Dan Fan gold.)

17 Apr 2022 Leave a comment

in General Posts Tags: can't buy a thrill, steely dan

Reprinted–nay, stolen from the band’s website whole cloth, out of fear it will be taken down there. (Hopefully they won’t force it to be taken down here. This is Dan Fan gold.)

02 Apr 2022 Leave a comment

in General Posts Tags: steely dan, the royal scam

(via CultureSonar) BY CAMERON GUNNOE

Hindsight bias is fascinating, particularly with students of a culture as opposed to those who experienced cultural events firsthand. Today, Steely Dan is regarded as two master craftsmen of studio sophistication – cynical jazz-heads with little patience for all but the cream of the musical crop.

The early-to-mid 1970s were a slightly different story, however. With the emergence of progressive bands like Genesis, Yes, and Jethro Tull, those not paying attention might have lumped Steely Dan in with any number of pedestrian rock bands of the day.

Sure, preemptive moves had been made to suggest the ultimate direction of the outfit. But as far as heady chords and swearing off the road, The Beatles had beaten them to the punch a decade earlier.

Today, listeners generally glean their interpretation of the Steely Dan “sound” from the group’s sixth LP, the high watermark, Aja. But during the first half of their career, a general pop audience may have been more likely to associate the group with their 1972 debut, Can’t Buy a Thrill…

13 Mar 2022 Leave a comment

in General Posts Tags: steely dan, steely dan outtake, the bear

Engineer Jay Marks’ comments: This is a rough mix that was made at Sigma Sound in New York the day Gary (Katz, producer) & Company came to check out our studio. I was the engineer. The tracks were cut by Al Schmidt except for the piano solo which I overdubbed that day.

The reason I know it’s my mix all these years later is because of the fade — Gary kept telling me to fade faster, and I was just too slow, never having heard the whole song before. So that’s why you hear that slight transition at the end — it’s not supposed to be there. (We also cut Kind Spirit that day as well as doing a rough mix on the “original lyrics” version of Third World Man, which at that time was called Were You Blind That Day.)

12 Mar 2022 Leave a comment

in Video of the Week Tags: steely dan, steely dan tribute

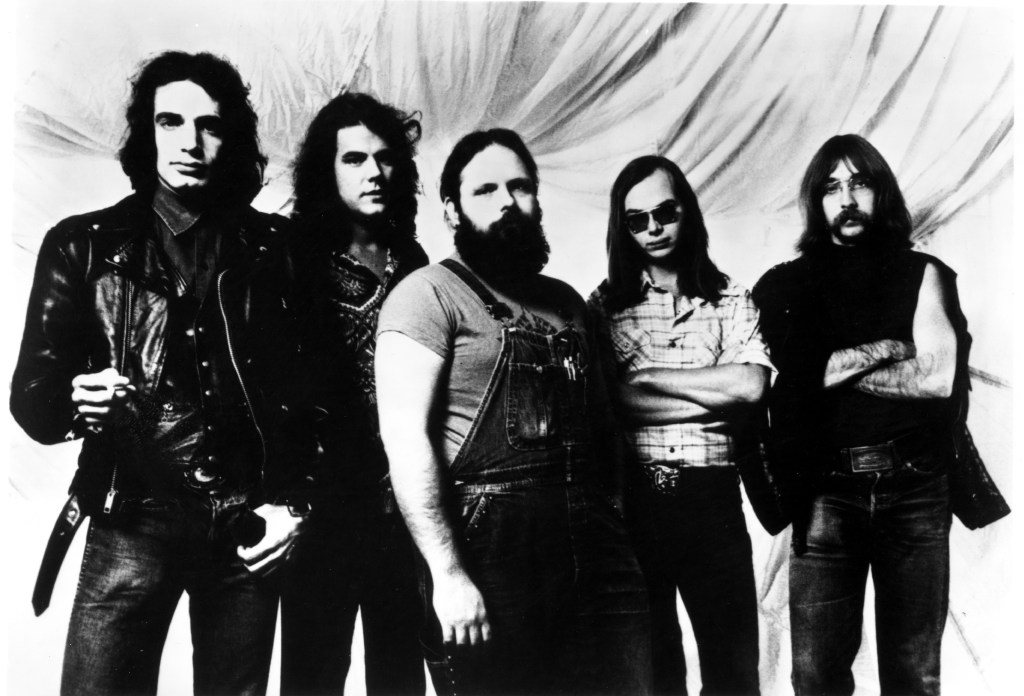

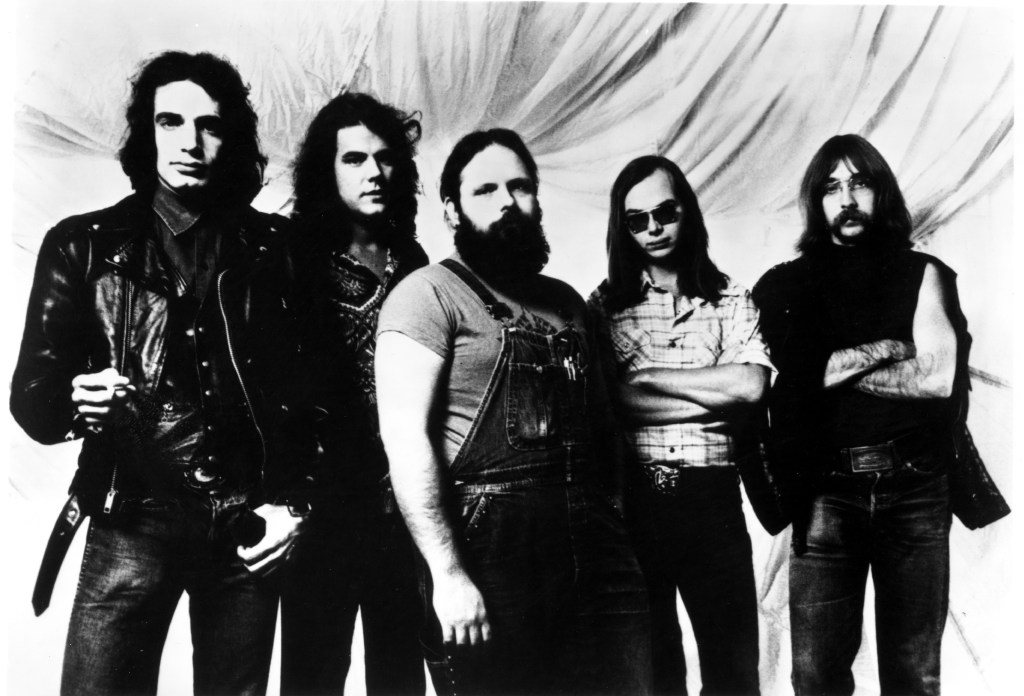

There are several excellent Steely Dan tribute bands out there. You can add the Brooklyn Charmers to that list.

Considering there are only five of them on the stage (I know you’re used to sixteen or more) these guys approximate Steely Dan classics–and choice deep cuts–remarkably well.

Wisely they don’t mess with the great original guitar solos. No band ever catalogued a greater collection of solos. And not tribute band ought to improvise their own or try to better them.

The only thing they lack is the thing every Dan tribute act lacks: the inimitable voice of Donald Fagen.

1:39 – Bodhisattva 6:46 – Peg 11:37 – Black Friday 15:55 – Turn That Heartbeat Over Again 21:43 – Kid Charlemagne 27:12 – Rikki Don’t Lose That Number 32:18 – Kings 36:18 – King Of The World 42:02 – Bad Sneakers 45:34 – Don’t Take Me Alive 50:24 – Midnite Cruiser 55:48 – Green Earrings 1:00:52 – My Old School 1:07:55 – Josie 1:13:59 – Hey Nineteen 1:21:52 – Boston Rag 1:28:36 – Reelin’ In The Years