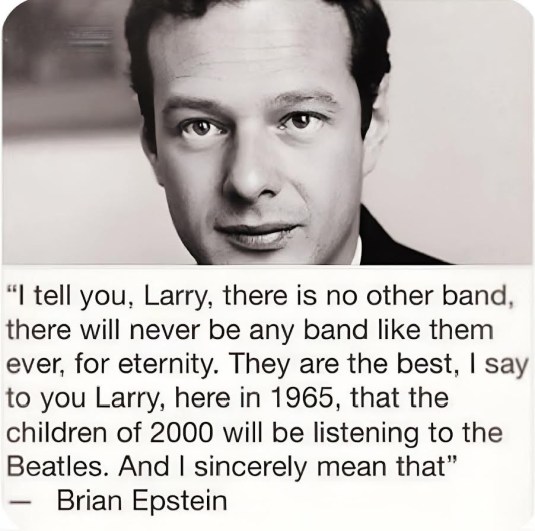

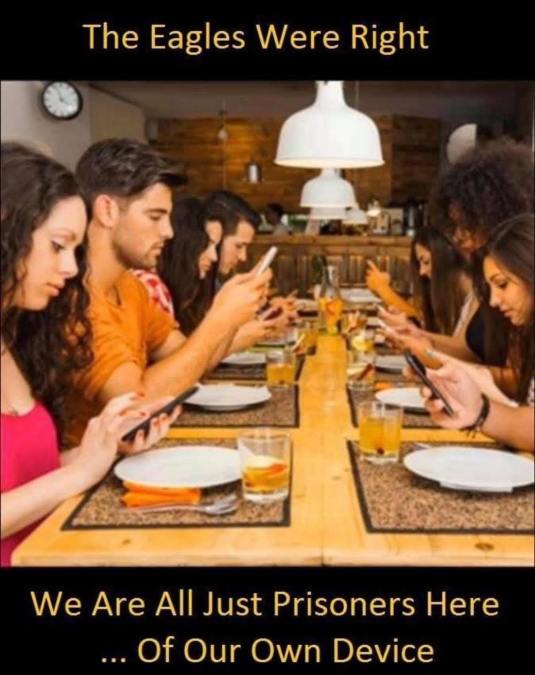

Every era of music has its standards; undeniable, indispensable, and ultimately inescapable cultural markers that live down the generations.

I don’t have to remind you that “Bohemian Rhapsody”, “Hotel California” and “Sweet Caroline” are as much a part of the 2020’s as they were part of the 70’s. You already know it, and so do your children–and maybe their children.

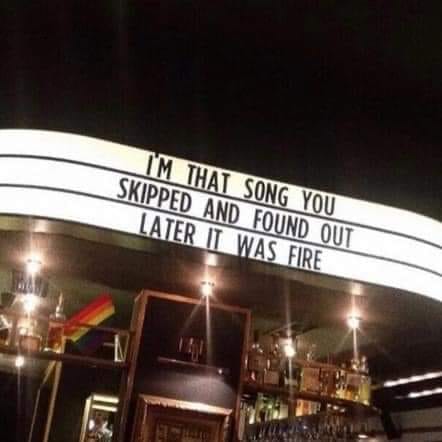

As much as classics like these deserve all the love and longevity, it’s not the thrust of this particular blog to celebrate the ubiquitous. In fact, mostly the focus here is to redirect the spotlight to the deserving but relatively overlooked songs or artists.

In the category of Songs You May Have Missed, we feature almost exclusively songs that never cracked the US Top 40 or were never singles at all.

The songs we recall here though were hits in their time, but didn’t live beyond it–or at least didn’t have the same afterlife of those universally acknowledged classics.

No mock operatic ambitions or snazzy guitar solos here. These songs have never been sung in a sports stadium.

They are just quietly devastating, tragically honest, perfectly arranged. These songs are transcendent. And, if you haven’t heard them lately, worth a fresh listen.

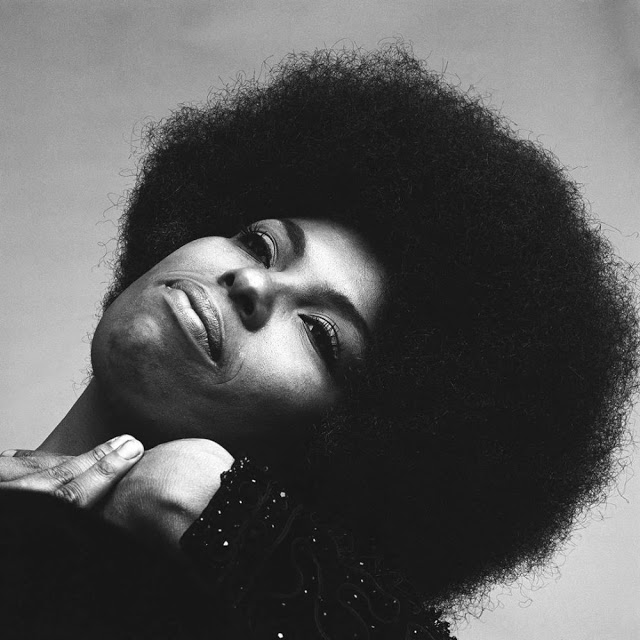

Roberta Flack: “If Ever I See You Again” (1978)

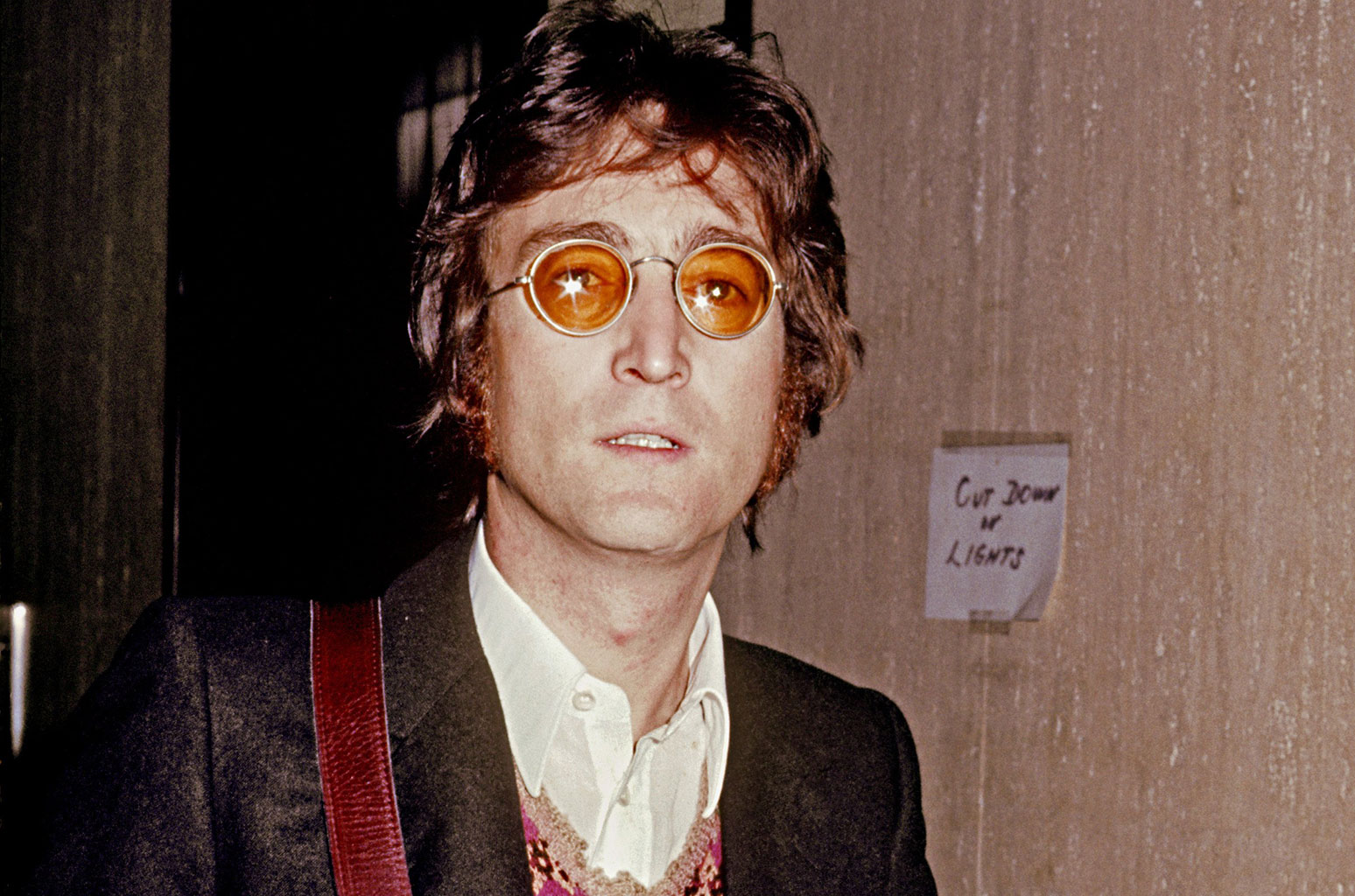

The 5th Dimension: “If I Could Reach You” (1972)

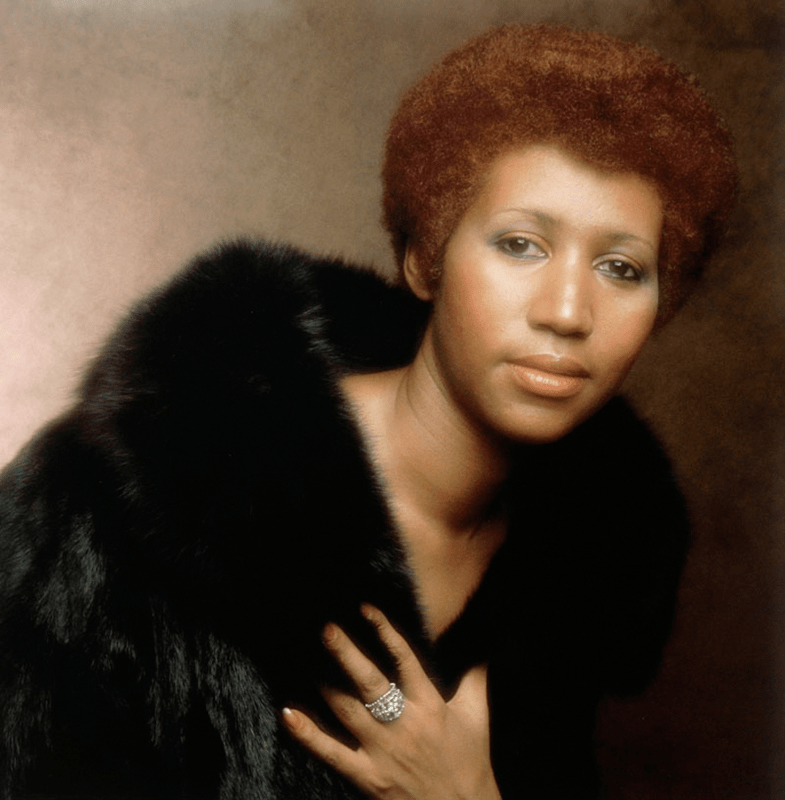

Aretha Franklin: “Until You Come Back to Me (That’s What I’m Gonna Do)” (1973)