Connie Converse: How Sad, How Lovely (2009)

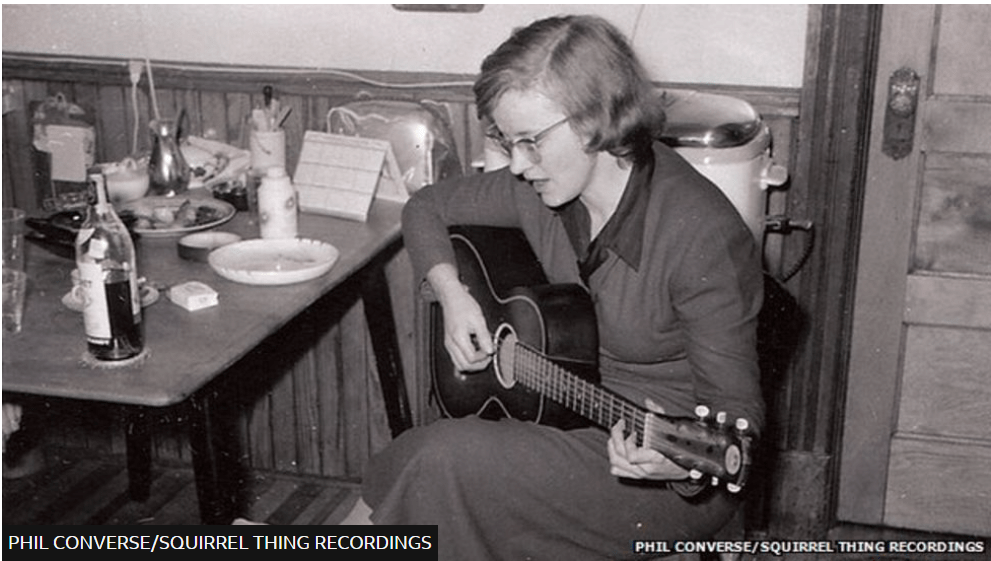

Connie Converse disappeared in 1974, leaving behind a haunting body of recorded music that would remain virtually unheard for the next 35 years.

Written through the 1950’s, Connie’s cache of original material instantly reveals itself to be uniquely inspired and years ahead of its time. (From Bandcamp artist bio)

Sure, the sheer mysteriousness of the Connie Converse’s story (explained in the video at page bottom) would be enough to intrigue: a brilliant student who dropped out of college, an enigmatic figure who seemingly dropped out of existence without a trace, a cache of songs forgotten and rediscovered 50 years later…a fascinating tale.

But this isn’t an unsolved mysteries blog, and we’d be content to leave the tale to other sites, but for one thing: Connie Converse’s songs are terrific.

The quality of the homemade recordings, not so much.

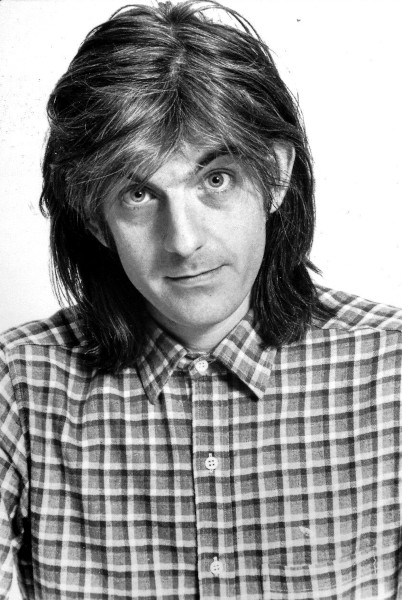

As Gene Deitch, who helped her record the tunes that would be discovered half a century later, surmised: “There were many better singers than Connie, but few were as intelligent or literate or beautiful. Her songs still haunt me.”

Indeed, as a writer Converse had a unique voice, a delightful way with wit, and a gift for the turn of phrase that would be the envy of many a folksinger.

Songs like “Roving Woman” and “Clover Saloon” also showed a feminist lyrical bent that was decades ahead of its time.

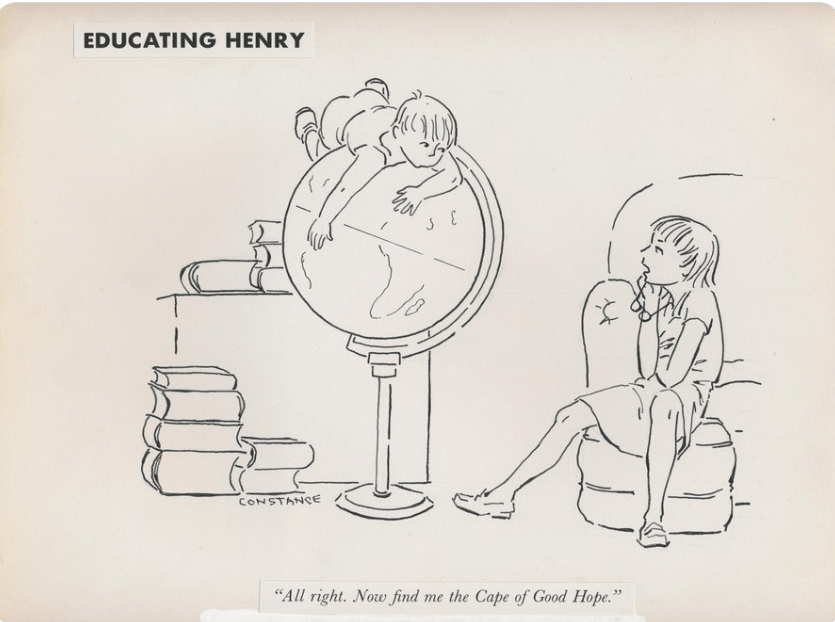

Moving to an apartment at 23 Grove Street in New York’s Greenwich Village area, Converse found work writing for academic journals and had cartoons published in the Saturday Review of Literature. She also enjoyed painting and writing poetry.

But it’s the songs she wrote and recorded at the Grove Street apartment, and at Deitch’s home, that will be her most lasting legacy.

Sadly however, it’s a legacy Connie Converse would not be around to enjoy. She gave up on the pursuit of music as a career, and moved from Greenwich Village the same year Bob Dylan arrived there, 1961.

Then in 1974, after health issues and bouts of depression, Connie Converse drove off in a Volkswagen Beetle, leaving behind written notes for family members and friends, including:

“Human society fascinates me and awes me and fills me with grief and joy. I just can’t find my place to plug into it. So let me go, please; and please accept my thanks for those happy times that each of you has given me over the years: and please know that I would have preferred to give you more than I ever did or could—I am in everyone’s debt.”

and:

“Let me go, let me be if I can, let me not be if I can’t”

Connie Converse was never heard from again, except in the rough and real recordings collected and finally released in 2009.

How sad, how lovely.

Listen to: “Talkin’ Like You (Two Tall Mountains)”

Listen to: “Johnny’s Brother”

Listen to: “Roving Woman”

Listen to: “The Clover Saloon”

Listen to: “Playboy of the Western World”